The Civil War and Reconstruction: A History of Hope, Betrayal, and Lessons for Today

How the Promise of Freedom After the Civil War Was Undermined—and What It Teaches Us About Justice Today

Introduction: Freedom’s Incomplete Revolution

The Civil War promised a new dawn for America—a rebirth of freedom and equality. But within a decade of its end, the forces of white supremacy and entrenched power had regrouped, leaving that dream in tatters. The failure of Reconstruction wasn’t just a missed opportunity; it was a deliberate retreat from justice, a pattern that echoes through American history.

In the last step of our journey, we explored how slavery—not “states’ rights”—drove the South to secede. Today, we take the next step by examining how the Civil War’s outcomes paved the way for Reconstruction’s promise, and why that promise was ultimately betrayed.

This is not just history—it’s a guide for understanding the challenges we face today. The forces that regrouped after Reconstruction’s collapse have resurfaced time and again, and it will take collective action to ensure they don’t win again. Your role in this journey matters. Together, we can uncover the truth, learn from the past, and work toward a better future.

The Civil War’s Outcomes: A Foundation for Change

The Civil War didn’t just end slavery. It shattered the illusion that America could survive while denying freedom to millions of its people. The Union’s victory marked a turning point, but the country’s deep divisions didn’t disappear overnight. Rebuilding a nation torn apart by inequality and violence was always going to be hard. But the war created a chance—brief as it was—to do just that.

A War of Consequences

As we explored in the last step of our journey, the Civil War was fought over slavery—plain and simple. The Confederate states seceded to protect their economy and way of life, both built on human bondage. When the Union triumphed, slavery was abolished. But the war left behind massive devastation, especially in the South, where entire cities were burned, economies collapsed, and millions of freedpeople faced an uncertain future.

The Role of Media

The press played a powerful role in shaping how Americans understood the war and what came next:

In the North: Publications like The Liberator and New York Tribune rallied support for emancipation but exposed deep divisions over what freedom should look like.

In the South: Even before the war ended, Southern newspapers began building the “Lost Cause” myth, painting the Confederacy as noble and downplaying slavery’s role in the war.

These narratives set the stage for Reconstruction, shaping how Americans—North and South—viewed the country’s next steps.

The Reconstruction Amendments

The Civil War brought some of the most transformative legal changes in American history:

The 13th Amendment abolished slavery but allowed involuntary servitude as punishment for a crime, creating a loophole for future exploitation.

The 14th Amendment granted citizenship and promised equal protection under the law, but enforcement was anything but guaranteed.

The 15th Amendment guaranteed Black men the right to vote, but violence and discriminatory laws quickly undermined that promise.

These amendments created a foundation for equality—but they were only as strong as the nation’s will to enforce them.

The Freedmen’s Bureau

In 1865, the Freedmen’s Bureau was established to help freedpeople transition from slavery to freedom. Its goals were ambitious: education, healthcare, and land redistribution. But the challenges were overwhelming:

Political Resistance: Southern leaders accused the Bureau of overreach and fought to defund it.

Economic Exploitation: Land promised to freedpeople was returned to former Confederate landowners by President Andrew Johnson, forcing many into exploitative sharecropping.

Violence: Schools and offices were attacked by white supremacists, who threatened anyone trying to create a better life.

Despite these barriers, the Freedmen’s Bureau helped lay the groundwork for education in Black communities. But its broader mission was systematically sabotaged.

Reconstruction’s Promise Meets Relentless Resistance

For a brief moment, Reconstruction brought a glimmer of hope. Federal intervention in the South created opportunities for Black Americans to vote, hold office, and build thriving communities. It was a glimpse of what a fairer, more equitable America could look like. But that progress wasn’t just resisted—it was met with a vicious backlash. White supremacists organized to dismantle these gains, ensuring that power and control stayed firmly in their hands.

The High Point: Radical Reconstruction

The Reconstruction Acts of 1867 divided the South into military districts, placing it under federal control. For the first time, Black men voted in large numbers, and many were elected to political office—some at the federal level. Schools, churches, and businesses flourished in freed communities. These were hard-won victories, built from the ground up, showing what could be possible when justice and opportunity were prioritized.

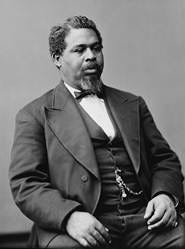

Black leaders like Robert Smalls exemplified the courage of Reconstruction. Smalls, who escaped slavery by commandeering a Confederate ship and delivering it to Union forces, joined the Union army and later served in Congress. Despite enduring death threats and violent opposition, Smalls never stopped fighting for the rights of freedpeople. "My race needs no special defense… all they need is an equal chance in the battle of life," he famously said. His determination and bravery inspired others to step forward, even in the face of relentless intimidation.

But for every step forward, there were relentless efforts to push back. White supremacists saw this progress as a threat to their dominance, and they were prepared to do whatever it took to stop it.

The Backlash: The Rise of White Supremacy Movements

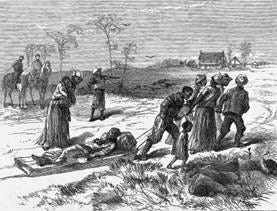

The progress made during Reconstruction was met with violence and terror, calculated to strip Black Americans of their newfound freedoms. White supremacist groups like the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) didn’t just appear—they were organized to enforce white dominance through fear and brutality.

Tactics of Terror: The KKK targeted Black voters, politicians, and allies with lynchings, beatings, and arson. These weren’t random acts of violence; they were deliberate campaigns to destroy political power and keep Black communities in fear. One of the most horrific examples was the Colfax Massacre of 1873 in Louisiana. Armed white supremacists attacked a group of Black men defending a courthouse, killing more than 150. It was one of the worst acts of racial violence during Reconstruction.

A Shared Agenda Across Classes: Wealthy elites and poor whites, though divided by class, united against Black progress. Landowners feared losing economic control, while poor whites saw freedpeople as competitors for jobs. This shared investment in white supremacy created a powerful, enduring alliance that worked to suppress Black communities at every turn.

The Federal Response—and Its Limits

The federal government initially tried to fight back. The Enforcement Acts of the early 1870s were designed to curb KKK activity and protect Black voters. These laws made some progress, but the effort was short-lived. As Northern interest in Reconstruction faded, so did the political will to confront white supremacist violence. By the mid-1870s, federal intervention had all but disappeared, leaving freedpeople vulnerable to escalating attacks.

Economic Exploitation: Sharecropping and Convict Leasing

Even as they gained formal freedoms, most freedpeople were trapped in cycles of economic exploitation:

Sharecropping: Black families were forced into agreements with white landowners that kept them in perpetual debt. These arrangements ensured that landowners remained in control while freedpeople had no path to independence.

Convict Leasing: The 13th Amendment allowed forced labor as punishment for a crime, creating a loophole exploited by Southern states. Black men were arrested on minor or fabricated charges, then leased to private businesses for brutal, unpaid labor. This system re-created slavery under another name, ensuring that white elites could continue to profit off Black labor.

These economic systems were designed to preserve the South’s racial hierarchy, ensuring that the promise of freedom remained out of reach for most freedpeople.

Education as a Battleground

Education became one of the central fights of Reconstruction, symbolizing both freedom and resistance. For freedpeople, schools represented a chance to build better futures for their families and communities. For white supremacists, schools were a direct threat to their control.

Logistical Hurdles: Building schools in the South was an enormous challenge. Resources were scarce, federal funding was inconsistent, and the sheer scale of the need overwhelmed the Freedmen’s Bureau and Northern charities. But freedpeople didn’t wait for help—they acted. In countless communities, they pooled resources to build makeshift schools and hired teachers, even when they couldn’t afford desks or supplies.

Violence Against Schools: White supremacists didn’t just see schools as buildings—they saw them as battlegrounds. Black schools were burned, teachers were assassinated, and students were terrorized. These attacks were meant to send a message: education would not be tolerated. But even in the face of violence, teachers like Charlotte Forten risked their lives to educate freedpeople. Forten, one of the first Black teachers to work with freedpeople in the South, described the experience as both deeply rewarding and fraught with danger: “We were watched constantly, but I knew the work was worth every risk.”

Education as Empowerment: Despite the risks, Black communities fought fiercely to defend their schools. They understood that literacy was more than a personal achievement—it was a pathway to political power, economic independence, and resistance. In one South Carolina community, freedpeople built a school from scratch, using whatever materials they could find. "Learning to read felt like freedom itself," one freedman later recalled. For many, attending school wasn’t just a goal—it was an act of defiance against a system designed to keep them oppressed.

The importance of education wasn’t just symbolic—it was practical. Schools created new opportunities, helped freedpeople organize politically, and challenged the foundations of white supremacy. That’s why they were targeted so relentlessly. And that’s why, despite the odds, Black communities refused to give up the fight for education.

The Supreme Court’s Betrayal

One of the most devastating blows to Reconstruction-era progress in education came with the Supreme Court case United States v. Cruikshank (1876). The case arose after the Colfax Massacre, where federal charges had been brought against the white attackers. In its decision, the Court ruled that the federal government couldn’t prosecute individuals for civil rights violations, effectively gutting the Enforcement Acts. This ruling emboldened white supremacists, sending a clear signal that the federal government would not intervene to protect Black communities.

The combination of violence, economic exploitation, and judicial abandonment created a perfect storm. Education, which had been one of Reconstruction’s greatest achievements, became one of its hardest-fought battlegrounds—and one of its most enduring symbols of both hope and resistance.

Why Reconstruction Failed

Reconstruction didn’t fail because of bad luck or a lack of effort—it was deliberately sabotaged. The forces of white supremacy were never dismantled, and the refusal to confront entrenched power left freedpeople vulnerable. Economic exploitation and Northern indifference created the perfect environment for these forces to regroup and reclaim control.

Economic Context: The Persistence of Exploitation

The Southern economy had been devastated by the Civil War, but one thing didn’t change: its dependence on Black labor. While slavery was technically abolished, the systems that kept Black people under white control were quickly reimagined to serve the same purpose.

The Broken Promise of Land: The idea of “forty acres and a mule” offered hope for Black independence, but it was never fulfilled. Land redistribution, which could have given freedpeople a foundation for economic security, was fiercely resisted by Southern elites. Instead of redistributing land, President Andrew Johnson returned confiscated property to former Confederates, leaving freedpeople with nothing. Without land, most had no choice but to work for the same white landowners who had enslaved them.

The Sharecropping Trap: With no land of their own, freedpeople were forced into exploitative sharecropping arrangements. They rented land from white landowners in exchange for a share of their crops. On the surface, it seemed like a partnership, but in practice, it was anything but fair. Landowners manipulated contracts, charged exorbitant fees, and kept Black families in perpetual debt. Sharecropping wasn’t freedom—it was servitude by another name.

Convict Leasing: Slavery Rebranded: The 13th Amendment outlawed slavery, but it left a loophole: forced labor was still allowed as punishment for a crime. Southern states quickly took advantage, passing laws that criminalized minor offenses—often targeting Black men. Once arrested, they were leased to private businesses for backbreaking labor in brutal conditions. This system, known as convict leasing, generated profits for both states and businesses while re-enslaving thousands.

Northern Complicity: The North didn’t just look the other way—it benefited from this exploitation. Cheap cotton from the South fueled Northern textile mills, and the products of convict labor enriched Northern industries. There was little incentive for Northern leaders to enforce reforms that might disrupt these profitable systems. As long as the South kept producing, the North was happy to ignore the cost.

By failing to redistribute land and enforce economic justice, Reconstruction left freedpeople trapped in systems designed to keep them dependent and powerless. The South’s economic recovery came at the expense of Black autonomy, ensuring that the old racial hierarchies remained intact.

Northern Fatigue: A Nation Turns Away

While the South fought tooth and nail to destroy Reconstruction, the North simply lost interest. The commitment to racial equality—never universally strong—faded, and political priorities shifted.

The Economic Panic of 1873: The Panic of 1873 was a severe financial crisis that rippled across the nation, causing widespread economic hardship. As Northern businesses and industries struggled to recover, public attention shifted away from Reconstruction and toward financial stability. Expensive federal programs in the South became an easy target for cost-cutting, and many Northerners prioritized their own recovery over the struggles of freedpeople.

Racial Indifference and Fatigue: While Radical Republicans led the charge for Reconstruction in its early years, broader Northern support was always fragile. For many Northerners, the goal of the Civil War had been to end slavery—not to ensure racial equality. As the years dragged on, Reconstruction came to be seen as an expensive, exhausting burden. Even among former abolitionists, there was little appetite to fight for a vision of equality that they didn’t truly share.

The Politics of Abandonment: Reconstruction became a political liability. The Democratic Party, backed by Southern white voters and anti-Reconstruction sentiment, gained strength in Northern states. To maintain their grip on power, Republicans softened their stance on Reconstruction, eventually abandoning it altogether. This shift culminated in the Compromise of 1877, a backroom deal that resolved the contested presidential election in favor of Republican Rutherford B. Hayes. In exchange, Republicans agreed to withdraw federal troops from the South, effectively ending Reconstruction. It was a betrayal that left freedpeople to fend for themselves.

Without federal protection, white supremacist forces in the South consolidated power. Jim Crow laws, disenfranchisement, and systemic oppression followed, erasing much of the progress made during Reconstruction.

The Legacy of Reconstruction’s Failure

Reconstruction’s collapse wasn’t just a temporary setback—it was a foundational failure that allowed systemic racism and inequality to take root in America. The consequences of this failure didn’t end with the 19th century. They’ve reverberated through every era since, shaping the social and political landscape of the United States in ways we still feel today.

Media’s Role in Cementing the “Lost Cause”

The end of Reconstruction didn’t just mark the beginning of systemic oppression—it also marked the start of a campaign to rewrite history. Southern elites pushed the “Lost Cause” narrative, a carefully crafted ideology that reframed the Confederacy as noble, honorable, and misunderstood. This wasn’t just about pride—it was about power.

Public Memorials and School Curricula: Confederate statues and memorials popped up across the South, often decades after the war. These weren’t simple tributes to history—they were political symbols, erected during the rise of Jim Crow to reinforce white supremacy. At the same time, Southern textbooks painted a picture of the Civil War as a fight for states’ rights and described Reconstruction as a failure, blaming it on what they falsely claimed was Black incompetence and corruption.

Collaboration with Publishers and Filmmakers: Organizations like the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) worked closely with publishers to ensure history books taught their version of events. Popular culture played a role too. Films like The Birth of a Nation (1915) glorified the Ku Klux Klan, portraying them as heroes who saved the South from chaos. These ideas didn’t just linger in the South—they spread across the country, shaping national perceptions of the Civil War and Reconstruction.

The “Lost Cause” narrative was wildly successful. It became a national myth, embraced not just by Southern whites but by many in the North as well. It helped reconcile white Northerners and Southerners, but at a devastating cost: Black Americans were erased from the story of Reconstruction, and the lessons of that era were lost. This rewriting of history ensured that systemic racism remained deeply embedded in American institutions.

Patterns of Capitulation

Reconstruction’s failure set a dangerous precedent. It showed what happens when the federal government refuses to confront entrenched power. That pattern of capitulation didn’t end with Reconstruction—it repeated itself in later eras, with devastating consequences.

The Gilded Age: After abandoning Reconstruction, the federal government turned its back on economic justice too. Corporate monopolies grew unchecked during the Gilded Age, amassing immense power while exploiting workers—many of whom were Black or recent immigrants. Laissez-faire policies allowed industrialists to grow rich while laborers endured dangerous working conditions and poverty wages. The same reluctance to confront white supremacy during Reconstruction mirrored the government’s hesitancy to challenge economic exploitation in this era.

The Civil Rights Movement: The struggles of the mid-20th century showed just how deeply entrenched the systems of racial oppression created after Reconstruction had become. Segregationists in the 1950s and 1960s borrowed directly from Reconstruction-era tactics—voter suppression, economic retaliation against activists, and violent intimidation. Federal intervention was again necessary to fight these injustices, but it came only after decades of resistance and immense sacrifices by those on the front lines.

These patterns remind us that progress is fragile. Without sustained vigilance and enforcement, the forces of oppression will always regroup and find new ways to maintain their power.

The New Jim Crow

Reconstruction’s failure paved the way for nearly a century of legalized racial apartheid. Segregation, voter suppression, and economic disenfranchisement became the law of the land, codified by Supreme Court decisions like Plessy v. Ferguson (1896). Systems like convict leasing and the denial of land ownership kept Black Americans trapped in cycles of poverty and oppression. These mechanisms didn’t disappear—they evolved, laying the foundation for the systemic racism that persists today.

Why This Legacy Matters

Reconstruction’s failure isn’t just a chapter in a history book—it’s a lens through which we can understand the structural challenges America still faces. The same forces that undermined Reconstruction—disinformation, systemic inequality, and resistance to reform—have reappeared throughout U.S. history, from the Gilded Age to the Civil Rights Movement and beyond.

The lesson is clear: When we refuse to confront entrenched power—whether it’s white supremacy, economic exploitation, or disinformation—we allow it to evolve and grow stronger. The fight for justice requires more than hope—it requires courage, vigilance, and an unrelenting commitment to challenging these forces, no matter how deeply rooted they are.

Conclusion: Building on Reconstruction’s Lessons

Reconstruction is more than just history—it’s a mirror. It reflects the fragility of progress when entrenched power goes unchallenged and reminds us how easily disinformation, systemic inequality, and complacency can undo hard-won gains. The question now is: Will we heed its lessons, or will we allow history to repeat itself?

The freedpeople of Reconstruction teach us that progress requires courage and determination. They risked their lives to build schools, organize communities, and demand equality in the face of relentless violence and systemic opposition. Their efforts show us what’s possible when people refuse to accept injustice as inevitable. They didn’t just dream of a better future—they fought for it, and their legacy calls on us to do the same.

Today, the fight continues. Disinformation, inequality, and the erosion of democratic principles remain formidable challenges, but so does the opportunity to resist them. Standing up to voter suppression, challenging systemic racism, and building communities rooted in justice and fairness are not just acts of defiance—they are acts of hope.

This journey we’re on—exploring our history to better understand how we move forward—requires all of us. Together, we can learn from the past and take the next steps toward a society that reflects the ideals of equality and justice.

If this mission resonates with you, consider supporting The American Manifesto. By becoming a paid subscriber, you’ll help ensure that these lessons remain accessible to everyone. Your support keeps this publication free for all readers and allows us to continue cutting through disinformation, uncovering the truth, and building a more just society. Sharing this article, having conversations about these lessons, and backing this work all make a difference in spreading knowledge and empowering change.

And this is just the beginning. Join us for the next chapter, where we’ll examine the Gilded Age and the rise of unchecked corporate power—an era whose echoes still shape our present. Together, we’ll continue to learn, question, and fight for the future we deserve.