The Freedom Illusion — Part I

How America rebuilt slavery without the chains

If you were selected at random from the American population, there’s a coin flip’s chance you’ll die with almost nothing.

Not because you didn’t work hard. Not because you made bad choices. Not because you weren’t smart enough or disciplined enough or American enough.

Because the system was designed that way.

The bottom 50% of Americans—165 million people—collectively own just 2.4% of the nation’s wealth.1 The average inheritance for the bottom half? $9,700.2 Not enough to pay off a used car. Not enough for a single semester of college tuition. Not enough to matter.

Meanwhile, the top 1% controls more wealth than that entire bottom half combined. Their average inheritance? $719,000.²

This isn’t a bug. It’s the blueprint.

Reader Advisory

This series is written more like a short book released in parts than a set of blog posts. Each installment is long, dense, and (at times) dark.

That’s not because the goal is despair. The goal is clarity—because hopelessness thrives when the pattern is felt but never named.

Please pace yourself. Read in chunks. Stop when you need to. Come back when you’re ready.

If you stick with it (even in chunks), this is what you’ll get:

A usable map + real receipts — the story of how the system was built, with specific “wait… what?” facts you can verify, share and even change minds with.

Pattern recognition that changes how you see the present — so chaos stops feeling random and starts looking like the predictable output of incentives and institutions operating as designed.

Language for hard conversations — a way to understand how ordinary people get pulled into harmful narratives (explanation, not justification) without instantly collapsing into partisan/culture-war traps.

Grounded hope + a strategy frame — proof the system is bendable, and a clearer sense of where leverage actually is: what must be constrained, what must be rebuilt, and what a real solution looks like if we actually want out of the extraction loop.

What This Series Is

Why does half of America work full-time and still struggle to survive? Why does every attempt to fix it—minimum wage fights, healthcare reform, student debt relief—get absorbed, reversed, or struck down? Why did the Voting Rights Act get gutted and Roe get overturned after decades of being “settled law”? Why do we know exactly what’s causing climate change but remain unable to stop it? Why are we more connected than ever yet lonelier than any generation before us? Why do movements fighting for justice keep losing ground even when they win individual battles?

And looking forward: must we accept that artificial intelligence will only further destabilize society—or could it be aligned toward something better?

These questions seem separate. They’re not. They’re all outputs of the same system.

This series traces that system from the ground up:

Part I exposes the economic architecture—how wage suppression, debt traps, and engineered crises keep 165 million Americans in permanent captivity

Part II examines the technologies of division—race, religion, culture—that prevent the people being extracted from uniting against those doing the extracting

Part III goes deeper—to the ideological level. How the way we understand society was deliberately reshaped over fifty years, with no counter-ideology ever built. The bipartisan surrender is the consequence, not the cause.

Part IV tallies the body count—deaths of despair, mass incarceration, epidemic loneliness, the authoritarian turn—and reveals what connects them: they’re not separate crises requiring separate solutions. They’re outputs of the same system. Treating them separately is precisely why we keep losing.

Part V answers the question that matters most: why do good policies keep failing, and what do we actually need to build if we’re going to win?

The first four parts are dark. Necessarily so. Comfortable assumptions have to be dismantled before the answer in Part V can land. If you want hope, it’s there—but you have to earn it by seeing what we’re up against first.

Let’s begin.

The Cage We’re All In

Some people will try to gatekeep slavery—insist the word only applies to colonial plantations and pre–Civil War chattel bondage. That move pretends to be “historically respectful,” but it’s really politically useful. It turns slavery into a museum exhibit: a specific costume, a specific era, a specific set of tools.

But slavery isn’t the costume. Slavery is the relationship: coercion dressed up as inevitability. A system where one class gets to live and build and pass wealth forward, and another class is kept permanently dependent—working, paying, bleeding, and dying with nothing to show for it.

Chattel slavery was uniquely brutal: the explicit legal ownership of human beings, enforced by violence, sanctified by law and religion. That exact form is gone. But the relationship didn’t disappear—it evolved. The mechanism updates: chains become contracts, auctions become credit scores, overseers become algorithms, and whips become the constant threat of homelessness, untreated illness, and financial ruin.

Neo-slavery is enforced economic captivity: you are “free” on paper, but coerced in practice—because the cost of refusing the terms is destitution. You’re kept dependent through wage suppression, unavoidable debt for necessities, and engineered crises that strip assets—so you can’t build or transfer wealth and must keep selling your life back to the system on terms you don’t set.

This is not a synonym for “life is hard.” It’s a specific condition: when a system makes saying no functionally impossible for large numbers of people—without catastrophic loss of shelter, health, legal standing, or basic survival.

Here’s the threshold. A society is drifting toward neo-slavery when most people are “free” in name but:

Exit is catastrophically expensive (lose your home, healthcare, custody, status, or future if you refuse the terms).

Survival is conditional (housing, medicine, education, and basic stability are gated behind compliance).

Debt is structural, not episodic (necessities require loans; interest becomes a permanent claim on your future).

Wealth-building is systematically blocked (every attempted foothold gets stripped by engineered crises, fees, and asymmetrical contracts).

When those conditions hold at scale, “voluntary” exchange stops being meaningfully voluntary.

It becomes compelled participation—economic captivity with paperwork.

I’m going to repeat this on purpose, because repetition is one of the ways the machine programs people, and we can use it too. In plain terms, it’s the same extraction with extra steps:

Wage suppression that divorces work from stability

Debt as discipline (housing, education, healthcare, credit)

Privatized emergencies that drain whatever you manage to save

Blocked exits—no real off-ramp, no real inheritance, no real security

Division as control—so you blame each other instead of the machine (more on this in Part II)

Call it something softer if you want. The outcome doesn’t change: your labor goes up, your freedom stays conditional, and your wealth—if it appears at all—gets vacuumed upward.

The following is one of those paragraphs the system makes unusually hard to write—because it has wired us to treat description as attack, and clarity as a provocation. It wants this to become a fight about identity instead of a recognition of design. I’m not taking the bait.

The key to understanding neo-slavery is this: racism isn’t separate from economic captivity—and neither is Christian fundamentalist politics. They’re tools the machine uses to enforce it. And if you’re looking for a single root cause—class or race or religion—you’re already stepping into the trap. This isn’t an “all suffering is the same” move. It’s the opposite: it’s naming how real differences in burden and treatment are manufactured, managed, and weaponized to keep the captive from uniting against their captors. Make no mistake: white supremacy and Christian fundamentalism had precursors before the extraction machine, but it was this machine that weaponized them, scaled them, and baked them into the rules of the game—profiting from them to this day. They don’t just coexist; they reinforce one another in a feedback loop: one builds a hierarchy of belonging that says who is “naturally” above whom; the other sanctifies that hierarchy and calls it virtue, order, even God’s will. Together they turn neighbors into threats, solidarity into suspicion, and shared captivity into a status competition. The gap between people in the cage isn’t the difference between freedom and slavery. It’s a managed gradient of suffering—designed to keep them fighting over rank inside the cage instead of building power to break it open together.

That’s the system. And you’re in it—wherever you sit.

If you’re reading this thinking “this doesn’t apply to me,” think again. Systems under sustained extraction don’t degrade gracefully. They collapse catastrophically. And when they do, your position in the hierarchy offers far less protection than you imagine.

This isn’t a threat. It’s not about fearing violence or hoping for revolution. It’s about acknowledging a pattern we see throughout reality: the more pressure builds in an unstable system, the more powerful the eventual release. Physicists call this self-organized criticality—the tendency of complex systems to evolve toward a critical state where small perturbations can trigger cascading failures. It applies to earthquakes, forest fires, neural networks, financial markets, and yes, societies.

The French aristocracy learned this at the guillotine—not because revolutionaries were uniquely evil, but because decades of extraction had loaded the system with pressure that eventually found release. The robber barons learned it when the banks collapsed in 1929 and their paper fortunes evaporated overnight—the market didn’t punish them out of justice, it simply couldn’t sustain the imbalance any longer. The wealthy today will learn it when climate disasters destroy their coastal properties, when infrastructure maintained by squeezed workers fails, when the instability they’ve been generating finally cascades beyond containment. The backlash doesn’t have to come from angry mobs. It can come from nature, from markets, from supply chains, from pandemics amplified by hollowed-out public health systems. The source doesn’t matter. The physics does, and it’s inevitable.

You cannot extract indefinitely from a system you’re embedded in. The damage to the social fabric eventually reaches everyone. The only question is whether we release the pressure deliberately through reform, or whether it releases itself catastrophically—taking everyone with it, including those who thought they were above the system.

Now let me show you exactly how it works.

The Closed Loop

Here’s how neo-slavery works. It’s elegant, really—if you can stomach the cruelty.

Step 1: Pay them just enough to survive.

Since 1979, American worker productivity has increased by 87%.3 If wages had kept pace—the way they did from 1945 to 1979, when productivity and pay rose together—the median worker would earn roughly $30,000 more per year than they do today.

Instead, wages for the median worker rose just 33% over those same four decades.³ The remaining 54 percentage points? Captured by the top. Extracted. Stolen in plain sight through “legal” mechanisms: union-busting, deregulation, tax cuts for the wealthy, the systematic dismantling of every policy that once ensured workers shared in the wealth they created.

Productivity went up. Your paycheck didn’t. That’s not an accident. That’s the architecture.

Step 2: Trap them in debt.

Total American household debt now stands at $18.59 trillion.4 That’s trillion with a T. The average household carries $105,000 in debt.⁴

$13 trillion in mortgage debt—because housing costs have been engineered to consume every possible dollar of your income

$1.61 trillion in student loans—because they made education the prerequisite for a middle-class life, then made it unaffordable

$1.23 trillion in credit card debt—because when wages don’t cover necessities, plastic fills the gap

Since 1980, college tuition has increased 1,200%—while overall inflation rose just 236%.5 The 1980s alone saw tuition spike 151%.⁵ The decade Reagan took office. Coincidence?

Healthcare premiums for middle-income workers jumped from 8% of take-home pay in 1980 to 25% in 2020.6 A quarter of your paycheck. Gone. Before you buy groceries, before you pay rent, before you save a single dollar.

This is the debt trap. It’s not designed to help you buy a home or get an education or stay healthy. It’s designed to ensure you never accumulate wealth. Every dollar you might save gets rerouted to interest payments, to premiums, to the endless extraction machine.

Step 3: Turn inevitable life events into extraction points.

Your parents get sick. Alzheimer’s, cancer, a stroke. Long-term care costs $128,000 per year.7 There’s no public system to help. So you drain your savings. Or they drain theirs—the home they spent 30 years paying off, liquidated in 18 months of nursing home bills.

Your kid gets into college. You want to give them the chance you had—or the chance you didn’t. So you co-sign the loans. You take out a second mortgage. You push retirement back another decade.

You get sick yourself. Even with insurance—especially with insurance—the bills pile up. The deductibles, the copays, the “out-of-network” surprises, the procedures they decide aren’t “medically necessary” after you’ve already had them.

Each of these is presented as a personal tragedy. Bad luck. A hardship. But zoom out and you see the pattern: these aren’t random misfortunes. They’re extraction points—engineered moments when whatever equity you’ve accumulated gets vacuumed up and transferred to the top.

Step 4: Ensure nothing transfers to the next generation.

The median inheritance in America is around $69,000.² But that number is a lie—skewed massively upward by the wealthy. For the bottom 50%, the typical inheritance is effectively zero.

This is the kill shot. This is where the loop closes.

Traditional slavery extracted wealth through labor. You worked, and someone else kept everything you produced. The system was transparent in its cruelty: you owned nothing, you inherited nothing, your children inherited nothing.

Neo-slavery achieves the same outcome with extra steps. You work, and you’re allowed to feel like you own things—a mortgaged house, a financed car, a 401(k) that looks impressive until you realize it won’t cover five years of retirement. But by the time you die, the system has reclaimed it all. The house sold to pay for care. The retirement account drained. The inheritance your children receive: not wealth, but debt. Not a foundation to build on, but a hole to climb out of.

The result is identical: generational wealth transfer is blocked for the many, guaranteed for the few. Your children start over from zero. Their children will too. Meanwhile, the families who owned capital in 1980 own even more capital today, and their grandchildren will own more still.

This is not capitalism. This is not free markets. This is extraction with American characteristics—a system designed to concentrate wealth at the top by ensuring it can never accumulate at the bottom.

The Math of Your Exploitation

Let’s make this concrete.

The Federal Reserve has tracked household wealth distribution since 1989. Here’s what three and a half decades of data show:

In 1989, the bottom 50% of Americans held 3.5% of national wealth.¹ Already an obscenity—half the country holding a sliver—but at least measurable. By 2011, that share had collapsed to 0.4%.¹ Point-four percent. The bottom half of America—160 million people—holding less than half a penny of every dollar. It’s since “recovered” to 2.4%, which means the bottom 50% now holds roughly two-thirds of what they held 35 years ago, despite working longer hours, taking on more debt, and producing far more value for their employers.

But the share of the pie only tells part of the story. Look at absolute dollars: between 1989 and 2018, the top 1% increased their total net worth by $21 trillion. The bottom 50%? Their net worth actually decreased by $900 billion.8 Not stagnation—negative growth. Three decades of work, and collectively, half of America ended up with less than they started with.

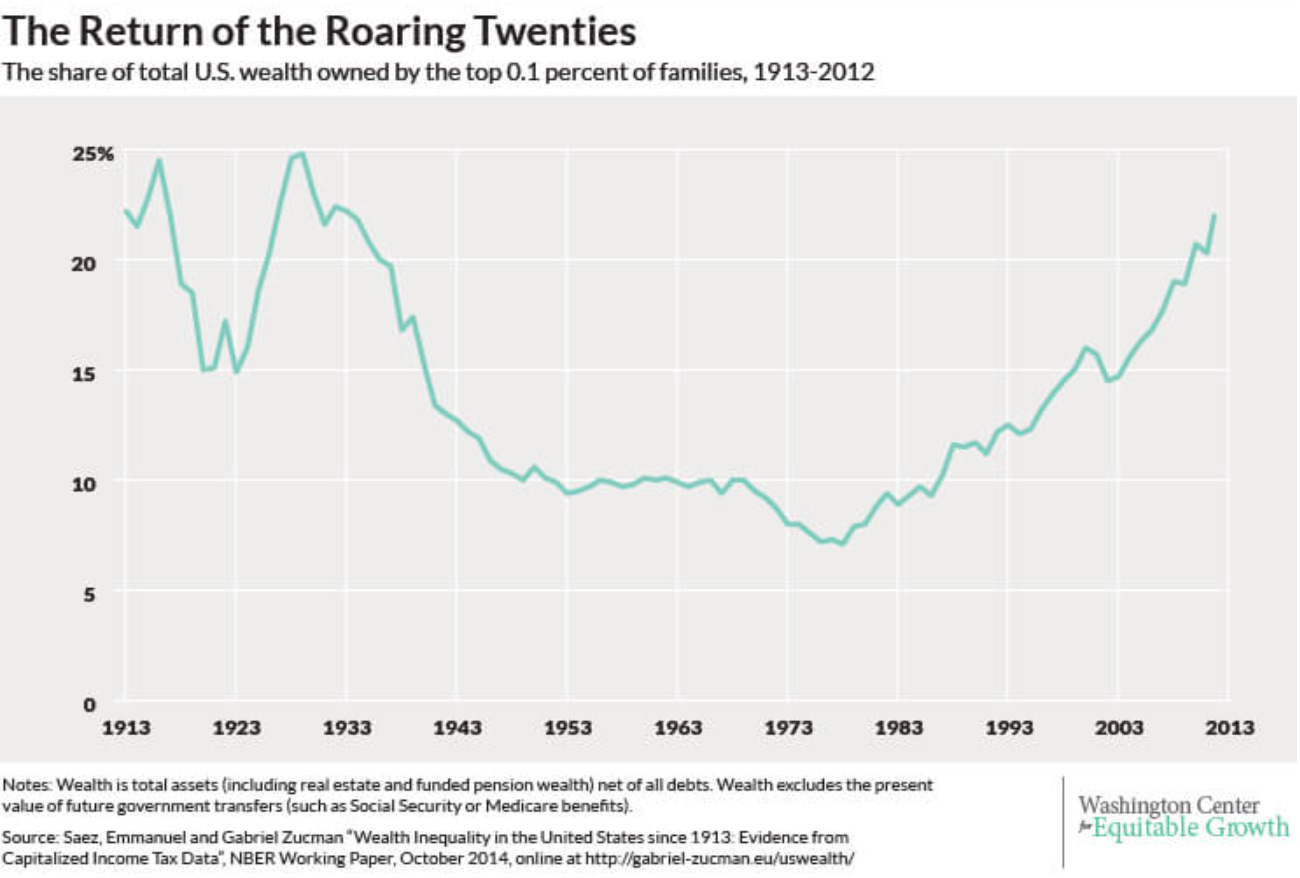

Zoom out further and the pattern becomes unmistakable. Wealth concentration has followed what economists call a “spectacular U-shape” over the past century—collapsing after the Great Depression, staying relatively flat through the postwar era, then rocketing back up starting in the 1980s. The top 0.1% have seen their wealth more than triple since 1980, returning to concentration levels not seen since the Roaring Twenties.⁸

This is what extraction looks like in aggregate. Not dramatic heists or obvious theft—just the slow, systematic transfer of everything you produce to people who already have more than they could spend in a hundred lifetimes.

What the Defenders Will Say

If you’ve read this far, you can already hear the objections. Let’s address them directly.

“But people DO get ahead. My grandparents came here with nothing.”

They’re right—individual exceptions exist. That’s how the con works. The system needs enough lottery winners to keep the losers playing. If nobody ever escaped, the game would be exposed. But zoom out: for every rags-to-riches story, there are millions who worked just as hard and died with nothing. The plural of anecdote isn’t data. The data says the bottom 50% has gained zero net wealth in 35 years.

“This is just how markets work. It’s not designed.”

The “free market” of Adam Smith doesn’t write laws, bust unions, cut taxes on capital gains while raising them on wages, or lobby Congress to make student debt non-dischargeable in bankruptcy. But the markets we actually have? They do all of that—because concentrated capital captured the government and called the result “the free market.” What we have isn’t markets doing market things. It’s oligarchy wearing a market costume. Every policy choice that built this system had authors, funders, and beneficiaries. We’ll meet them in Part II.

“People choose to take on debt. That’s personal responsibility.”

You “choose” debt the way you “choose” to breathe underwater when someone’s holding you down. When wages don’t cover rent, when education is the only path to a living wage, when a medical emergency can bankrupt you—debt isn’t a choice. It’s the only option left after all the other options were removed. The system creates the conditions, then blames you for responding to them.

“Calling this ‘slavery’ disrespects actual slaves.”

Chattel slavery was uniquely brutal—we said so above. But the deflection here is telling. When we call it “economic anxiety” or “inequality” or “the wealth gap,” nothing changes. The softer words let people nod sympathetically and move on. Neo-slavery is precise: it describes a system designed to extract labor while blocking wealth accumulation, enforced not by whips but by the threat of destitution. If the word makes you uncomfortable, ask yourself why—and whether that discomfort serves the people in the system or the people running it.

“So you want socialism.”

No. This isn’t a manifesto for socialism—it’s a manifesto for capitalism that actually works. Real capitalism: where markets reward innovation and effort, where competition is genuine rather than rigged, where the wealth generated by productivity flows to those who produce it rather than being siphoned upward through captured policy.

What we have now isn’t capitalism. It’s extraction wearing capitalism’s clothes. And the New Deal, for all its improvements, was still built on exclusion and lacked the foundational principles to sustain itself against the counterattack that began in the 1970s.

What I’m proposing is something more resilient: a Social Contract grounded in foundational values—fairness, truth, responsibility, merit, simplicity—that provide both guidance and protection against capture. Not socialism, not the current oligarchy, and not a return to a flawed past. Something built to last. Part V points to the detailed frameworks for those who want to see what that looks like.

The system has answers for every objection because it’s been refining those answers for forty years. But notice what all these defenses have in common: they locate the problem in individuals—their choices, their luck, their grit. The one thing they never do is question the machine itself.

The Freedom Illusion

The genius of this system—the thing that makes it more sustainable than chattel slavery ever was—is that it lets you believe you’re free.

You choose your job. (From a handful of employers who all pay the same suppressed wages.)

You choose your debt. (From a handful of lenders who all charge the same predatory rates.)

You choose your insurance. (From a handful of companies who all deny the same claims.)

You choose your apartment, your grocery store, your streaming service. You vote in elections. You post on social media. You have opinions.

And so you feel free. You feel like the outcomes in your life are the result of your choices, your effort, your character. When you fail to build wealth, it must be because you didn’t work hard enough, save enough, sacrifice enough. The system offers you the experience of agency while engineering the outcome of extraction.

This is the illusion of freedom. You’re not a slave—slaves know they’re slaves. You’re something more insidious: a “free” person who’s been convinced that their captivity is liberty, that their extraction is opportunity, that their poverty is personal failure rather than policy success.

The corollary is equally corrosive: if you do make it, the system tells you that was personal too. Your grit. Your choices. Your superior character. Not the zip code you grew up in—which determined the quality of your schools and your access to healthcare. Not the resources passed down by parents who benefited from policies that excluded others. Not the inherited wealth that traces back, somewhere in the chain, to slavery, convict leasing, redlining, or a thousand other policy decisions that lifted some by pushing others down.

This isn’t to say success is always undeserved or independent of effort. But where you start in the race, and what obstacles are placed or removed from your path, have a decisive impact on the outcome. The system needs you to believe otherwise—needs the winners to think they earned it alone and the losers to think they failed alone—because the alternative is seeing the architecture. And once you see it, you might start asking who built it and who it serves.

The chains aren’t made of iron. They’re made of debt statements and premium bills and tuition invoices and rental agreements. They don’t bind your body—they bind your future, and your children’s future, and their children’s future.

And the people who built this system? They call it the American Dream.

What Comes Next

This is Part I of a series. We’ve established what the system does—how it extracts wealth from the many to concentrate it among the few, how it blocks generational wealth transfer for everyone except those already at the top, how it maintains the illusion of freedom while delivering the reality of servitude.

In Part II, we’ll trace how we got here—the historical throughline from chattel slavery to sharecropping to convict leasing to mass incarceration. We’ll see how race and religion were weaponized to prevent class solidarity, how the New Deal briefly broke the pattern, and how the Republican Party launched a counter-offensive to rebuild the extraction system. The con has been running for four centuries. The costumes change; the mechanics don’t.

In Part III, we’ll address the Democratic surrender—how the party of FDR became the party of Clinton, how they capitulated to an economic model they should have fought, and the ideological trap that made them incapable of resistance.

In Part IV, we’ll document the consequences—the deaths of despair, the fraying social fabric, the turn toward authoritarianism when people lose hope in the system.

And in Part V, we’ll provide the map forward—a catalogue of the work that shows where we’ve been, how we got here, where our current path leads, and the alternative paths available to us.

The first step to breaking free is seeing the cage.

You see it now.

The question is: what are you going to do about it?

If work like this—documenting the architecture of your exploitation and naming the system that was designed to keep you poor—feels worth having in the world, please consider supporting The American Manifesto. Paid subscriptions make it possible to keep building the analysis that shows you exactly how they’re doing this to you.

Your Move

This piece makes a strong claim: that the American economy has been deliberately designed to extract wealth from working people and prevent generational advancement.

Does this framework match your lived experience? Where do you see the extraction points in your own life?

If you’re over 50, how does your economic trajectory compare to your parents’ at the same age?

What parts of this analysis do you think need more evidence? What would convince skeptics?

For those who disagree: where specifically is this argument wrong?

The comments are open. Let’s build this understanding together.

Federal Reserve, “Distribution of Household Wealth in the U.S. since 1989“, Federal Reserve Board, December 2024.

Federal Reserve data tracking the distribution of household wealth across different segments of the American population from 1989 to present. The data shows that as of 2024, the bottom 50% of American households held just 2.4% of total national wealth—down from 3.5% in 1990. This represents a decline of roughly one-third in the wealth share held by half the country over 35 years, even as total national wealth increased substantially. The same data shows the top 1% controlling 30.8% of national wealth.

Federal Reserve Board, “Wealth and Income Concentration in the SCF: 1989–2019“, FEDS Notes, September 28, 2020.

Analysis of Federal Reserve Survey of Consumer Finances data examining inheritance patterns across income groups. The research found that the median inheritance was $69,000, but this figure obscures massive disparities: the average inheritance for the wealthiest 1% was $719,000, while the average for the bottom 50% was just $9,700. This tenfold-plus disparity in inherited wealth demonstrates how the current system perpetuates wealth concentration across generations.

Economic Policy Institute, “The Productivity-Pay Gap“, Economic Policy Institute, Updated 2025.

Comprehensive analysis of the divergence between worker productivity and compensation since 1979. The research documents that economy-wide productivity grew by 87.3% between 1979 and 2024, while median worker compensation rose just 32.7%—a 54.6 percentage point gap. The analysis identifies specific policy causes: deregulation, union-busting, erosion of the minimum wage, corporate-led globalization, and tax cuts for high earners. Critically, the research notes that from 1948-1979, productivity and pay rose together, demonstrating this divergence is policy choice, not economic inevitability.

Federal Reserve Bank of New York, “Household Debt Balances Grow Steadily; Mortgage Originations Tick Up in Third Quarter“, Federal Reserve Bank of New York, November 5, 2025.

Quarterly report on household debt levels from the New York Federal Reserve. As of Q3 2025, total household debt reached a record $18.59 trillion. The breakdown: $13 trillion in mortgages, $1.61 trillion in student loans, $1.23 trillion in credit card debt (also a record), and $1.56 trillion in auto loans. The average household carries approximately $105,000 in total debt. These figures support the article’s argument that debt has become the mechanism of extraction in the modern economy.

Education Data Initiative, “College Tuition Inflation Rate“, Education Data Initiative, 2025.

Comprehensive analysis of college tuition increases over time, adjusted for inflation. The data shows that since 1980, college tuition and fees increased 1,200%, while the Consumer Price Index rose just 236%. The 1980s—the Reagan decade—saw the most extreme tuition inflation in history: a 151.2% increase in just ten years. This deliberate policy of defunding public education and pushing costs onto students and families created the $1.61 trillion student debt crisis.

Willis Towers Watson, “The Big Paycheck Squeeze: The Impacts of Rising Healthcare Costs“, WTW, July 2023.

Analysis of healthcare’s growing burden on worker compensation. The research found that healthcare premiums for middle-income workers (fifth decile) jumped from 8% of take-home pay in 1980 to 25% in 2020. Additionally, of approximately $12,000 added to average worker total compensation between 2000-2020, only 46% went to cash wages—the majority was absorbed by rising health insurance costs. This demonstrates how healthcare costs function as an extraction mechanism, capturing wage gains before workers ever see them.

Genworth Financial, “Cost of Care Survey“, Genworth, 2024.

Annual survey of long-term care costs across the United States. The national median cost for a private room in a nursing home is $127,750 annually ($350/day), with costs significantly higher in many metropolitan areas. The survey documents how these costs—largely uninsurable and not covered by Medicare—function as a wealth extraction mechanism, forcing families to liquidate assets accumulated over decades to cover end-of-life care.

Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman, “Exploding Wealth Inequality in the United States“, Washington Center for Equitable Growth, October 20, 2014.

Landmark research documenting wealth concentration’s “spectacular U-shape” over the past century—with inequality now approaching 1920s levels. The authors found that wealth of the top 0.1% “more than tripled between 1980 and 2012,” while “the average wealth of the bottom 90 percent of families is equal to $80,000 in 2012—the same level as in 1986.” The key driver: top 1% families save roughly 35% of income while the bottom 90% save approximately zero. More recent Federal Reserve analysis confirms that “Families in the Bottom 50 group have always held less than 5 percent of total wealth, and the share has been close to 2 percent since 2010.” A People’s Policy Project analysis found that between 1989 and 2018, the top 1% increased their total net worth by $21 trillion while the bottom 50% actually saw their net worth decrease by $900 billion.

All societies have created hierarchies from the beginning of recorded time Since we humans are merely animals who have attained a level of consciousness we behave like animals who also are biologically observed to have hierarchies

But since we are conscious animals we develop a sense of right and wrong That leads to laws and a judicial system It's all well and good to this point in evolution

In any animal society human or otherwise there is always the biological innate demand for survival In this context any human society equates this survival to money But this survival tool becomes so twisted and obfuscated that it renders over timelines what we have today which is an ever increasing wealth gap And this becomes even more unmanageable in a society due to greed and power

We are fast approaching the societal inflection point of self imposed criticality by creating a currency crisis of the West's own making by ushering in a fiat currency system in 1971 when the US dollar went off a gold standard which had restrained government spending in excess The global economy will implode in the near future(2026?) and those societies like China with 70K tonnes of gold will survive better than others But this should be not surprising It has happened over and over again in society after society in the timeline of history

Irresponsible governments who don't learn this important fiscal lesson will continue to disrupt and eventually destroy the very societies they lead, whether democratic or not And the people they govern will pay the price in what is written about slavery without chains and the servitude it creates Of course even if restraints are imposed on the government there is always the avarice, greed, and desire for power that is innate human ego desires that trap the conscious human animals that we are on the material plane and prevents us from achieving our spiritual potential which truly separates us from unconscious animals

Thank you. This resonated with me.

I remember when I was newly married and complained to my husband that I realized that, because of my asthma, I would always be a slave to the system. How else would I ever get healthcare for my meds?

I always assumed I would not have an inheritance. My parents were tricked into a reverse mortgage. When my father's heart and dementia made them need to downsize, they were left with less than half of the sale of my childhood home. That was last year. This year the rent at their senior living went up and my mother lives in fear of running out of money. My father's health continues to decline.

I look forward to the rest of your series.